Door Monitoring Americastestkitchen/metricution

Going to the bathroom is something we all do on a daily basis. At ATK we have shared single person unisex bathrooms, which makes finding an open bathroom difficult at times. It’s by no means the largest problem that needs solving, but it was a problem that involved a hardware solution, thus capturing my personal interest.

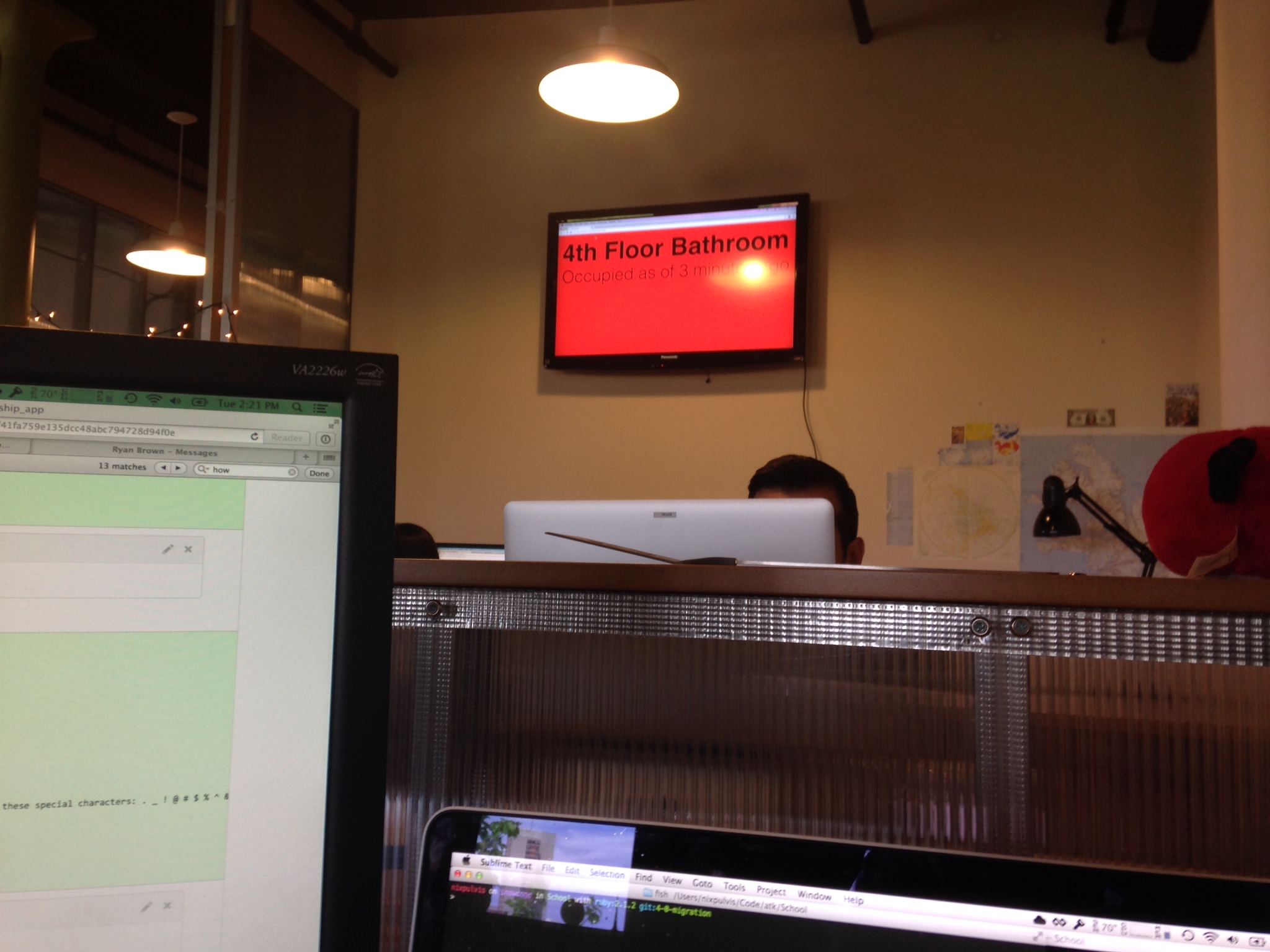

This is the view from my work area, as you can see it’s very easy to tell when it’s safe to run to the bathroom now, thanks to our bathroom status monitor.

To tackle this problem I opted for the following technologies.

The Concept

Whenever someone uses a bathroom in our office they close the door (obviously), but more importantly, when they are finished they leave the door open. In the past the door being open has been a sort of signal for availability. This application leverages this preexisting protocol to implement a simple bathroom status monitor. The data is collected from the Spark Core equipped with a magnetic door sensor Reed switch. The door sensor can tell when the door is closed or open, that’s it. When the door is closed we say the bathroom is occupied, and when the door is opened we say the bathroom is available.

The Nitty Gritty

This project’s code is pretty simple, broken into two very discrete parts. The backend, and the frontend. Both live on GitHub and are there for your viewing pleasure.

The Spark Core

The Spark Core is a very cool little device. It’s very small yet has an on-board WiFi module. This makes it perfect for inter-office status reporting. The WiFi in our building reaches pretty much 100% of the space, so it’s a simple way to send data to and from a server. This allows for the status hardware to communicate directly with the webserver. Solutions involving other forms of radio communication need a dedicated hardware for receiving messages and forwarding them to the webserver.

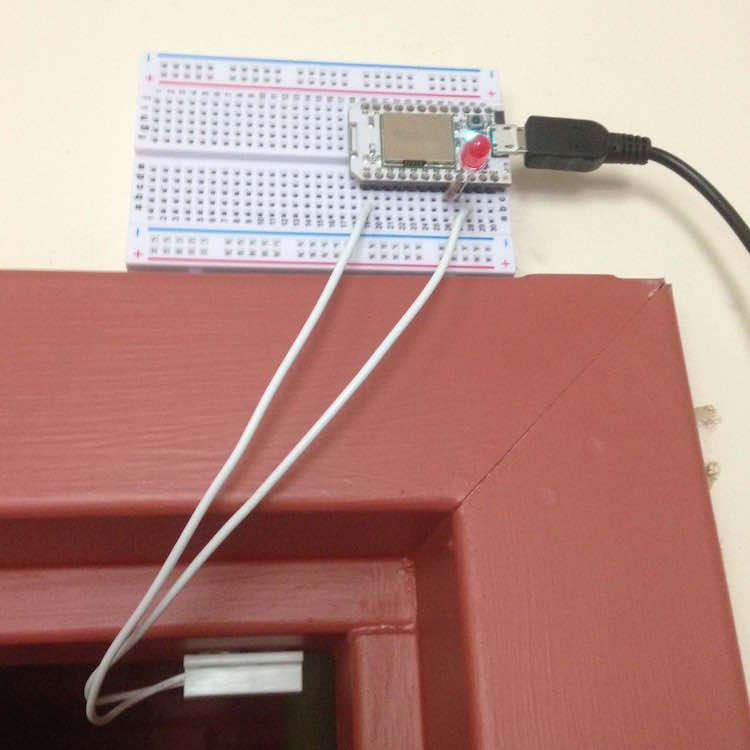

The photo above is the current setup. As you can see it’s dead simple, just a Spark Core with a Adafruit Magnetic Contact Switch (door sensor) and an LED. We don’t even need resistors for the sensor because we are making use of the internal pull up capabilities of the core.

Sending events with the Spark Core is simple, in fact the whole firmware for this project fits easily below. To understand it better refer to the excellent Spark Core documentation.

// State

// 0 = Available

// 1 = Occupied

int state;

int last_state = state;

void setup() {

pinMode(D7, OUTPUT);

pinMode(D0, INPUT_PULLDOWN);

char *version = "0.0.4";

Spark.variable("version", version, STRING);

char *ssid = Network.SSID();

Spark.variable("ssid", ssid, STRING);

state = digitalRead(D0);

Spark.variable("state", &state, INT);

Spark.publish("door", (state ? "closed" : "opened"), 60, PRIVATE);

}

void loop() {

state = digitalRead(D0);

if (state != last_state) {

digitalWrite(D7, state);

Spark.publish("door", (state ? "closed" : "opened"), 60, PRIVATE);

}

last_state = state;

}Communication between all of the cores and our webserver happens over a single persistent HTTP connection, using Server Sent Events, thanks to the Spark Cloud. To leverage this I needed to write a very basic SSE client in Ruby.

Getting Data to The Browser

Getting the data to the client is the next trick, luckily we can do the same thing we did to get it to the server. Server sent events have a browser implementation called EventSource that allows us to register events in the browser. When a user connects to the server asking for the bathroom status they get an Ember app that sets up a EventSource connection to the server’s SSE bathroom API, and updates it’s internal representation of the bathrooms when the server sends an event. The code for this is very simple with Ember.

source = new EventSource('/api/v1/events/bathrooms')

source.addEventListener 'bathroom', (event) =>

@get('store').pushPayload('bathroom', JSON.parse(event.data))When the process monitoring the Spark Core’s events picks up a change in their status it updates the database and sends a Redis event. Doing this in Rails is easy.

class Bathroom < ActiveRecord::Base

...

after_save do

Metricution::Redis.publish('bathroom', Metricution::ActiveRecordSerializer.to_json(self))

end

endThen the controller in Rails is relatively simple.

def bathrooms

sse = Metricution::SSE::Writer.new(response.stream)

# TODO: Use one Redis connection. Creating a full

# Redis connection per request is pretty expensive.

redis = Redis.new

redis.subscribe('bathroom') do |on|

on.message do |channel, message|

sse.write(message, event: 'bathroom')

end

end

# Rescue user closing connection.

rescue IOError

logger.into "stream closed"

# Clean up the action.

ensure

redis.quit

sse.close

endAnd just like that we have live updating data in Ember from a Spark Core.

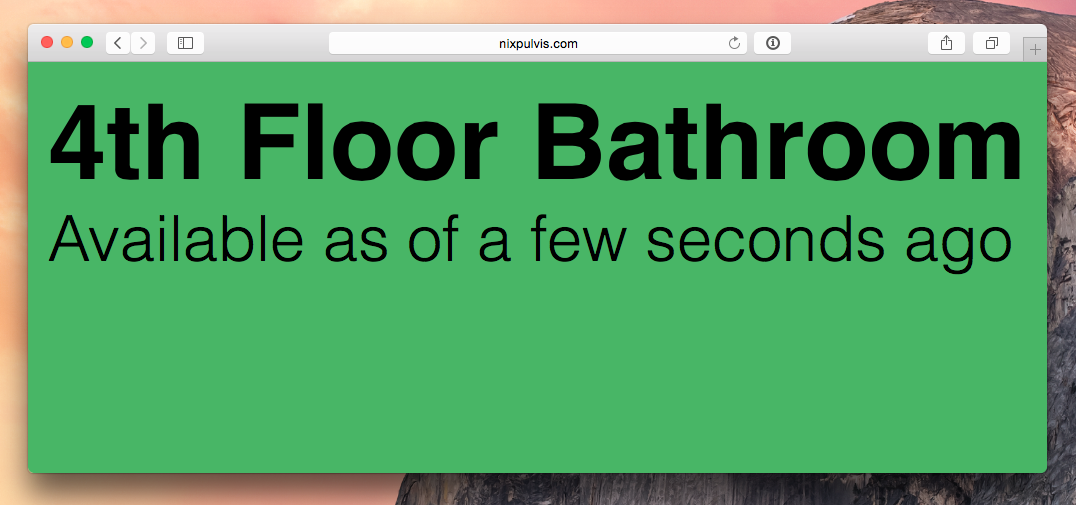

The Frontend

Simple, flat, and to the point. Backed by ember, it updates in realtime, and updates font sizes to take up as much space as it can. Keeping everything very large allows it to be useful when put up on screens for the whole office.

All in all this project is relatively simple, but it’s saving time in failed trips to the bathroom. The next step involves complex analysis of historical bathroom visit data, to allow for statistical insight into bathroom habits. Oh, and a 💩 icon for when the bathroom has been occupied for more than 5 minutes.